Every six or seven years, sand is pumped onto Tybee Island’s beaches to counteract natural erosion caused by waves, tides, wind and human activity. Since the last nourishment was completed in early 2020, researchers in Director Clark Alexander’s lab at the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (SkIO) have been monitoring the shoreline and creating detailed maps to help guide future nourishment projects.

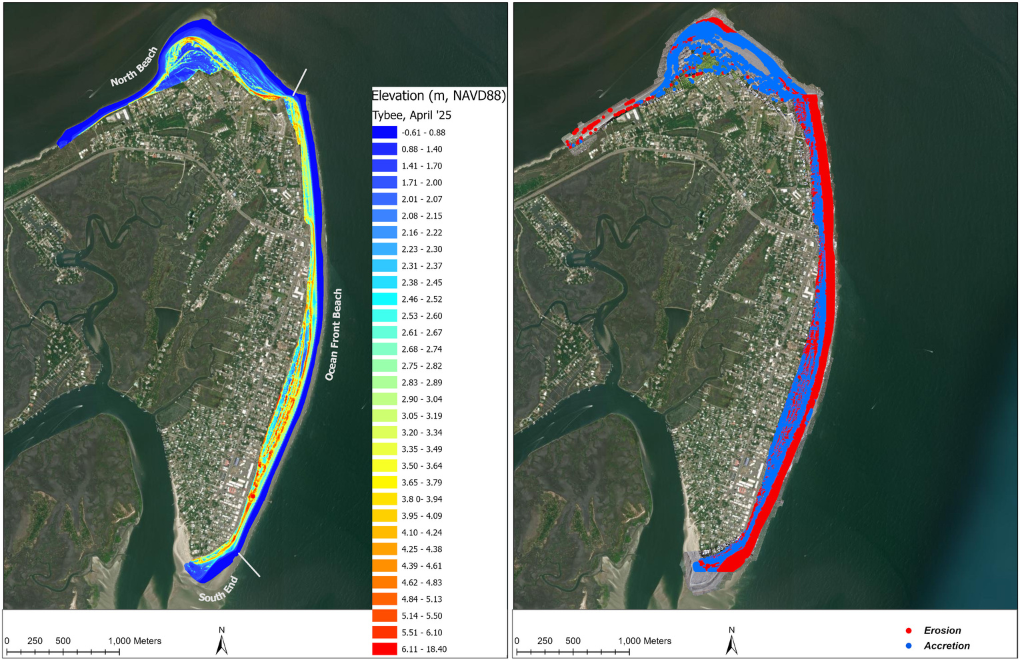

Claudia Venherm, a research professional in Alexander’s lab, flies a LiDAR drone over the island’s publicly accessible beaches every three months and after major storms. Her maps show patterns of erosion and accretion at each section of the beach over time.

The data is compiled and presented twice a year to City of Tybee officials, who use the information to inform the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) on where sand needs to be placed.

“Because of SkIO’s data, we know for a fact, since the last beach nourishment, where it is eroding, where it is accreting, and how fast it has been eroding,” said Alan Robertson, who manages beach nourishment projects for Tybee. “That informs the Corps in their template and informs the design of the beach. I take a lot of pride in the fact that the Corps is using our data, provided by Skidaway, in the design.”

Since 1975, USACE has periodically nourished Tybee’s beaches, covering a significant share of the costs. They do this because the Corps’ maintenance of the shipping channel leading into the Port of Savannah disrupts the natural flow of sediment from the north that would otherwise help replenish Tybee’s beaches.

For the first 45 years of USACE’s partnership with Tybee, the Corps focused solely on building a flat, wide beach by pumping sand to a pre-planned design width. But in 2020, USACE added extra sand at Tybee’s request that the city used to create a complete row of dunes as well. Dunes serve as natural barriers, guarding Tybee’s community and infrastructure from potential storms and hurricanes.

“People hadn’t created dunes for the purpose of protecting against storm damage in the state of Georgia before,” said Alexander, who is also a professor in the Department of Marine Sciences at UGA’s Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “These were functional dunes to provide sacrificial sources of sand if we had high sea levels and intense storms. This was the city being very proactive.”

Initially, Tybee brought the Alexander Lab on to monitor the new dunes. But after clear signs the dunes were stable, the project grew to include the full beach profile.

As Venherm flies the drone, Research Professional Mike Robinson walks along the beach with a real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS system, which works in conjunction with the LiDAR drone to improve the accuracy of the geospatial data the drone collects. Kyle Krezdorn, also a research professional in the Alexander Lab, monitors the drone as it flies.

“What we are trying to do is see the changes,” said Venherm. “I measure the elevation of the beach and the dunes and look at how that changes every three months. And then I can say if there is erosion or accretion of sand.”

Venherm has found that erosion is most prominent near the bend where Highway 80 becomes Butler Avenue. Since March 2020, the stretch of beach facing the Atlantic Ocean, along with the south end, has lost more than 260,000 cubic meters of sand. However, the dunes have gained nearly 30,000 cubic meters — likely due to wind carrying sand inland, where vegetation helps trap and hold it in place.

In addition to informing USACE about where to pump sand, having the SkIO reports helps inform and build confidence and trust in the public, whose tax dollars help fund the nourishment projects, Robertson explained.

“The other benefit of this is, now that we have five years of data, we can start to project,” said Robertson. “We can tell the public ‘here’s where you can expect there to be no beach next summer season at high tide.’ We can get ahead of that. We don’t have to be reactive.”

With insights from the SkIO reports, the City of Tybee is working with USACE on developing the plans for a new beach nourishment, currently scheduled to start in November 2026.

About SkIO

The UGA Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (SkIO) is a multidisciplinary research and education institution located on Skidaway Island near Savannah, Georgia. The Institute was founded in 1967 with a mission to conduct research in all fields of oceanography. In 2013, SkIO was merged with the University of Georgia. The campus serves as a gateway to coastal and marine environments for programs throughout the University System. The Institute’s primary goals are to further the understanding of marine and environmental processes, conduct leading-edge research on coastal and marine systems, and train tomorrow’s scientists. For more information, visit www.skio.uga.edu.