The August cruise for DolLAYER in the Gulf of Mexico is officially complete. We were at sea from August 13-26 and had excellent weather almost the entire time. The whole team of 13 scientists worked hard to capture the zooplankton community during a highly stratified time of the year. The goal for this cruise was to measure the abundances of different zooplankton with imaging and couple that with stable isotopes and molecular gut content analysis to see the connection between vertical oceanographic structure, distributions of organisms, and their diets. Overall, we want to see if conditions that are vertically stratified favor more gelatinous dominated food webs.

The northern Gulf of Mexico shelf during summertime is a classic “layer cake” with different oceanographic properties. The surface is usually very warm from the hot summer sun, and it is also quite fresh (i.e., low in salinity) due to the heavy amounts of river discharge into the area. The deeper waters are salty and cooler, but that can change from place to place. We made measurements from the Florida shelf all the way over to the Louisiana Bird’s Foot Delta, capturing lots of different layers and even hypoxia (low oxygen conditions that tend to form in the summertime Gulf).

The ocean gave us ideal weather for shipboard operations and also another animal we were looking for – doliolids! They were really abundant especially near the center of our sampling efforts just south of Mobile Bay, Alabama. Some might even say there was a bloom of doliolids. This gave opportunities for several graduate students to perform feeding experiments on doliolids, their predators, and resolve the doliolid microbiomes. Below is a picture from the modular Deep-focus Plankton Imager (mDPI) showing what it looks like inside of the doliolid bloom. This image is 9.1 cm wide by 6.0 cm tall, and you are looking through 25 cm of ocean water. There are 2 different life stages of doliolids in the image, and this corresponds to an abundance of ~2900 doliolids per cubic meter! Some of the smaller squiggly organisms are appendicularians – a cousin to the doliolid and an important prey item for larval tunas.

To capture zooplankton for diet analysis and experiments, we tow this large system called the MOCNESS. That stands for Multiple Opening and Closing Net Environmental Sensing System. That is a mouthful, but this instrument is incredibly powerful because we can open and close nets below, within, and above different layers and understand exactly what the different zooplankton are eating and their connection to the vertical structure in the ocean. Below is a picture of a MOCNESS deployment. There is a motor near the top of the instrument that rotates and drops that stack of bars, one at a time, which closes one net and opens another. On the ship, we can see the exact depth of the MOCNESS and open and close nets to correspond to different layers. If you want to know more, here is a video explaining how the MOCNESS works.

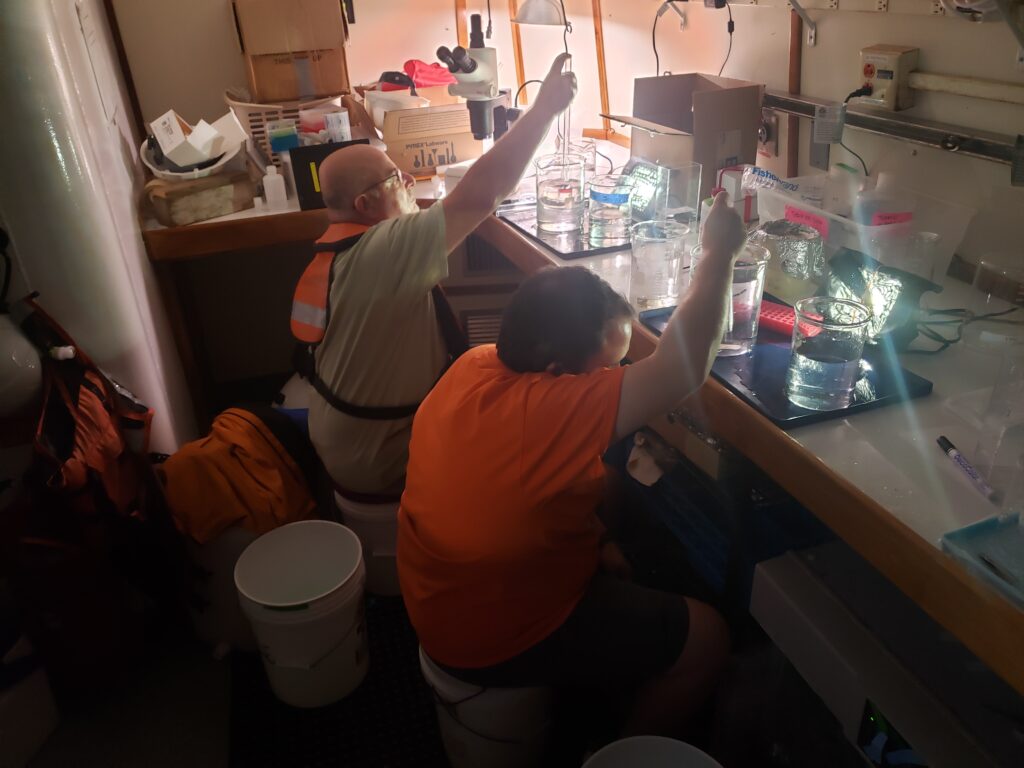

Once the MOCNESS is back on the ship, that is when the fun begins. We dump the contents of the nets into 5-gallon buckets and carry them into the “wet lab” on the ship. Below is the #1 ranked “picking team” on the RV Savannah. They sit in this dark room with jars and special lights to help them see the different gelatinous animals, and they meticulously pick out different organisms for diet and stable isotope analyses. This is helping us resolve the ocean food web and understand who eats who, and what the different organisms are doing in different parts of the ocean “layer cake.”

We tow our mDPI behind the ship to get the precise location of individual zooplankton and see how the “layer cake” varies among the different sampling stations. Here are Grace and Nele at the computer flying the mDPI. We get a live feed of all the different sensors on the vehicle from the screen on the right, which includes temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll-a fluorescence (a proxy for phytoplankton abundance), and PAR (photosynthetically active radiation, or simply the amount of sunlight penetrating the ocean to the location of the mDPI). The best part is that we also see a live feed from the camera on the left screen, so when a cool animal or a bunch of doliolids fly across the screen, it can be really exciting! We like to call it “Plankton TV.”

One treat of being at sea (in addition to the excellent food prepared by Chef Ben) is seeing sunsets/sunrises, storms in the distance, and wildlife. We saw lots of dolphins, seabirds, big jellies, and a hammerhead shark. Below is a picture of our mDPI sitting upright with a beautiful sunset over the calm Gulf waters. We will be back out in the same environment in about 2 months to see how everything has changed. Thanks to the science and ship crews for a successful expedition in the Gulf!